SUMO: A Landmark Revisited

By Philippe Garner

Helmut always demonstrated a healthy disdain for easy or predictable solutions. SUMO—a bold and, certainly within the traditions of photography, an unprecedented publishing venture—was an irresistible project. The idea of a spectacular compendium of images, reproduced to exceptional page size and to state-of-the-art origination and printing standards, emerged from an open, exploratory dialogue between photographer and publisher. Helmut liked to probe possibilities, ever eager to rethink the ways in which he could develop and extend the all-important interface between his work and his audience. The magazine page had been the constant on which he had built his career; from the mid-1970s, books and exhibitions offered further opportunities, allowing him to exploit more extended picture sequences and significant changes of print scale. Here, with the physically commanding SUMO, weighing in—boxed and shrink-wrapped—at 35.4 kilos, Helmut created, at the close of the 20th century, a landmark book that would stand head and shoulders above anything that had been attempted conceptually or technically before. SUMO, complete with its bespoke lectern, set an ambitious new standard—a book with the dimension of a private exhibition.

SUMO might also be interpreted as a triumph of another order, with a very particular political and cultural significance that made it a singularly emotive and gratifying achievement. For here was a forceful statement, implicit rather than baldly stated—and all the stronger for that—confirming the authority of an unusually gifted individual’s perspective and emphatically marking his determination to engage an audience on his terms—in short, a statement about freedom of expression.

Helmut ranks among the foremost figurative artists of his era. A social commentator of exceptional insight, his was a distinct and surprising sensibility—perverse, with a sharp and insistent curiosity, perfectly leavened by wry humour. Helmut’s talent was uniquely personal and he had the ability to turn into a valuable creative resource everything that he experienced, including the turmoil of those formative years in which brutal and traumatic political realities disrupted all that had been agreeable and stable in his life. An at-first reluctant exile, he adapted imaginatively to his itinerant destiny. Helmut developed a finely calibrated sensitivity to the atmosphere of place and to everything he observed—notably to the subtleties of social codes and rituals and to the visual language of seduction and of style. He took inspiration from his nostalgic fondness for the evocative symbols of old Europe, the Europe of his youth; and he embraced with fascination the vulgar New Babylons of the U. S., particularly Los Angeles. As he matured, he learned to use that matchless eye and twisted perception to create a body of work that is to its age as significant a document as are, for instance, the satirical caricatures of William Hogarth to the excesses of 18th-century Britain, the drawings of Honoré Daumier to the social nuances of French life in the mid-19th century or the savage visual dissections of George Grosz to the decadence of that very Berlin into which Helmut was born.

Helmut truly found his form once he settled in Paris. There, he defined for himself a creative role within a chic high Bohemia, the milieu of interlinked friends and professional associates in the worlds of fashion, the media and the arts that was the stimulating crucible for his work. In his rue Aubriot studio in the 1970s, he stored his Kodachrome transparencies in small cabinets labelled “Fashion”, “Erotic subjects” and “Portraits mondains”; but of course his genius was to wilfully blur these distinctions, building a multilayered social portrait in which subtle allusions and telling undercurrents lent every picture intrigue and reverberation.

Helmut travelled widely, but always carried with him the precious and poignant memories of his native Germany; and these feelings drew him back with increasing regularity to the country and culture that had shaped him. There was an irresistible logic in the fact that the four issues of Helmut Newton’s Illustrated that he produced between 1985 and 1995 should take their inspiration from then-new photo-illustrated journals that had inspired him in the 1930s. Germany could boast a long and significant tradition in the story of publishing, since the flowering of printing in the pioneering era of Johannes Gutenberg; and Helmut had, at first hand, witnessed its tragic corollary with the repression and the book burning of the Nazis. This observation calls to mind Helmut’s cool-headed response some years ago to the report that a lecture he had been invited to deliver to a university audience would be disrupted by a group of students planning to throw raw meat at this speaker, whose work they were only prepared to perceive through the prism of their own rigid prejudices. Helmut’s judicious opening remarks situated him immediately as one who was lucky to have escaped the increasingly vicious purges of the late 1930s and who had surely earned the right to freedom of artistic expression—and the right, as a working photographer, to challenge and to provoke. The student anger was defused and by the end of his talk all were ready to offer up their resounding applause for an artist with the courage and tenacity to pursue his creative instinct to the full and who, through his witty, sophisticated and confrontational images, was determined to throw down the gauntlet against the mediocre, the safe and the superficial.

SUMO, appropriately published in Germany, has made its memorable statement as a piece of photobook history. Its size and consequent costliness, however, inevitably limited its diffusion. This new edition is the fulfilment of an ambition conceived some years ago by Helmut. He would surely be pleased that, a decade on from its first publication, SUMO—now in a format that allows for a more democratic distribution—will reach the widest possible audience.

Images

1/2: Paris, December 1998:

Philippe Starck working on the

design of the stainless steel SUMO

table at his studio.

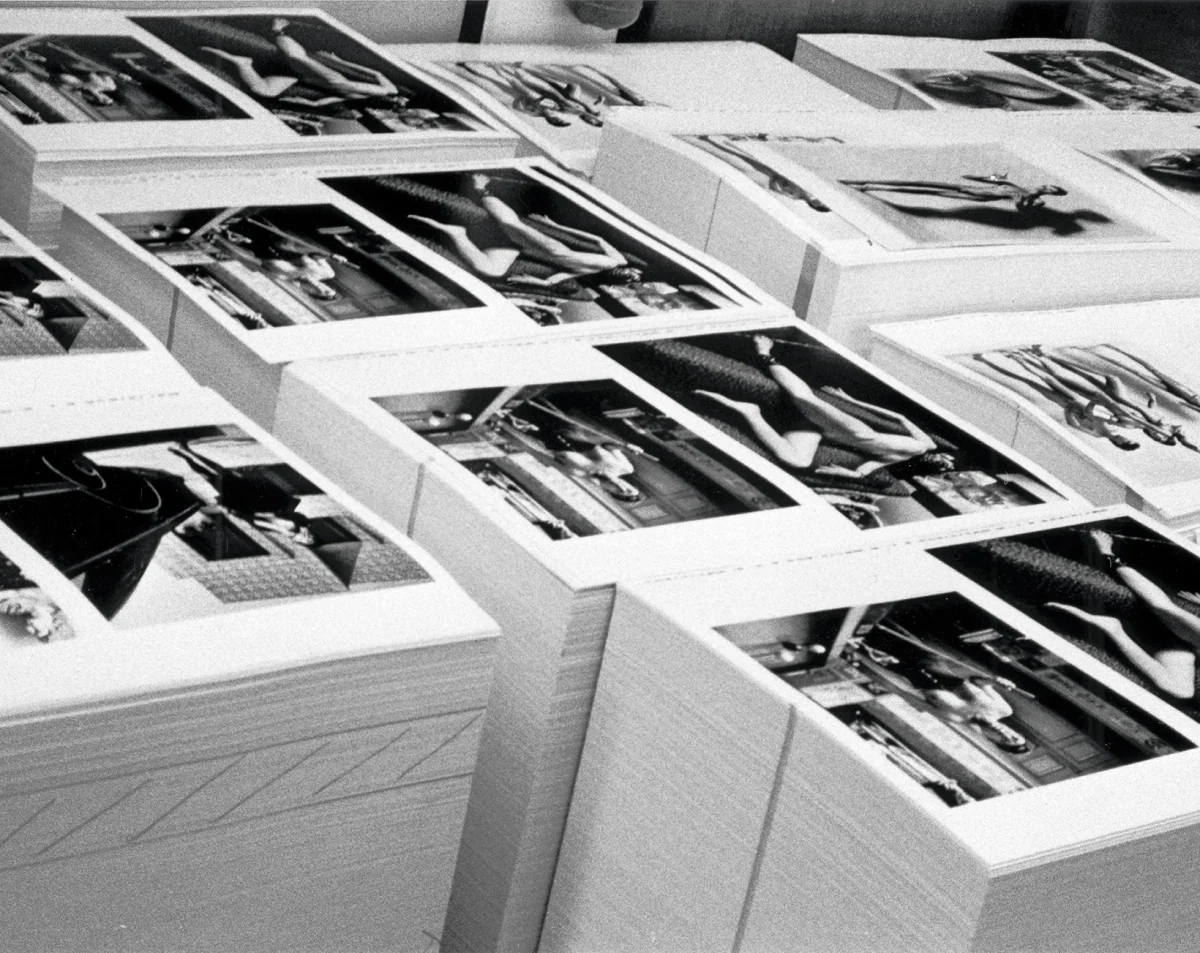

3: Milano, May 1999: Huge piles of SUMO printing sheets waiting to be bound at Legatoria LEM, an italian bookbindery for oversized books including rare bibles for the Vatican. Over 350 tons of 250 g/qm BVS-Plus paper, manufactured for SUMO by Papierfabrik Scheufelen, were needed at the printer Editoriale Bortolazzi in Verona over a period of three months.